About the Book House of Swann (Forthcoming)

How the True Story of the First Drag Queen Was Uncovered

About This Short Film

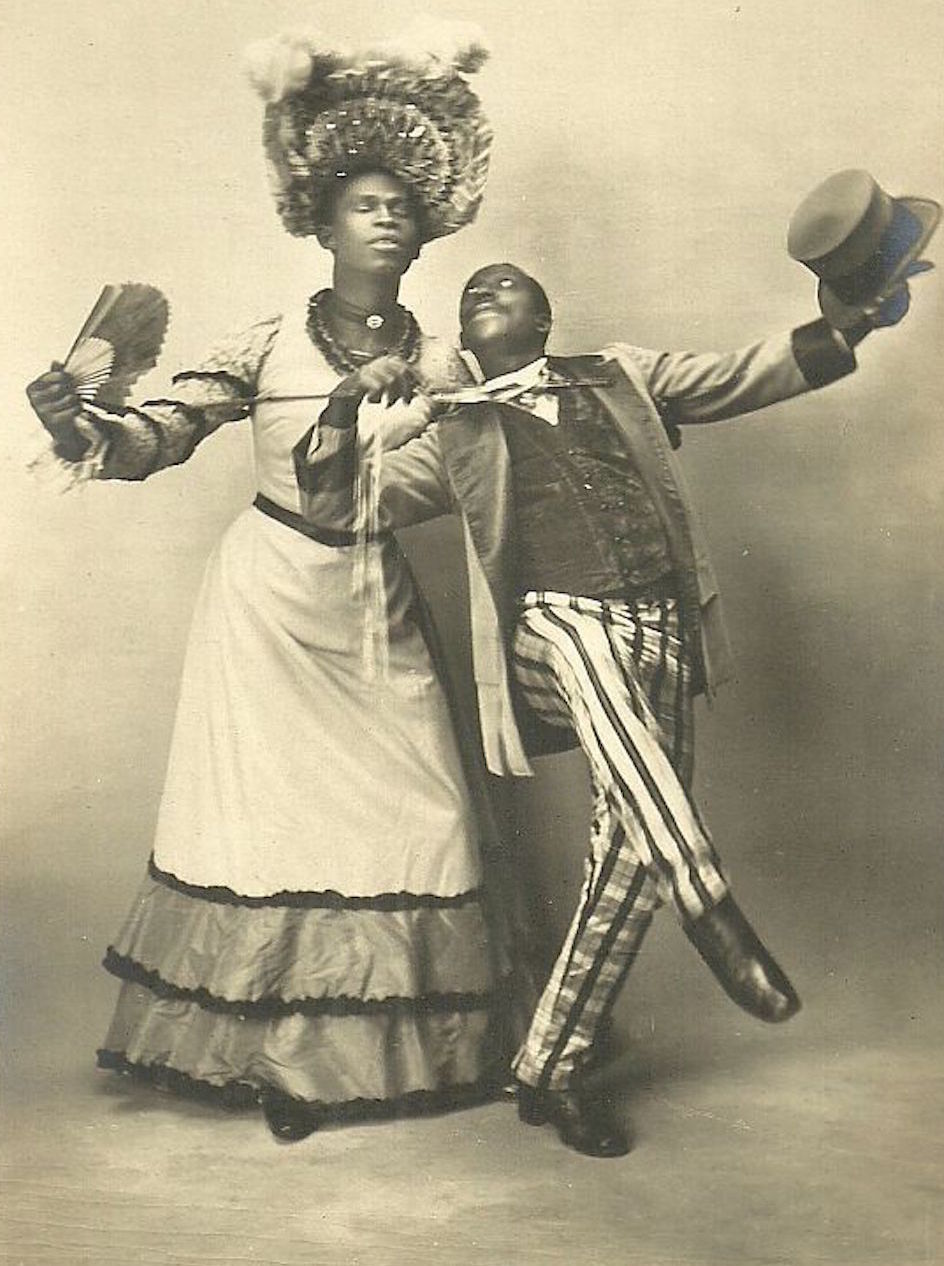

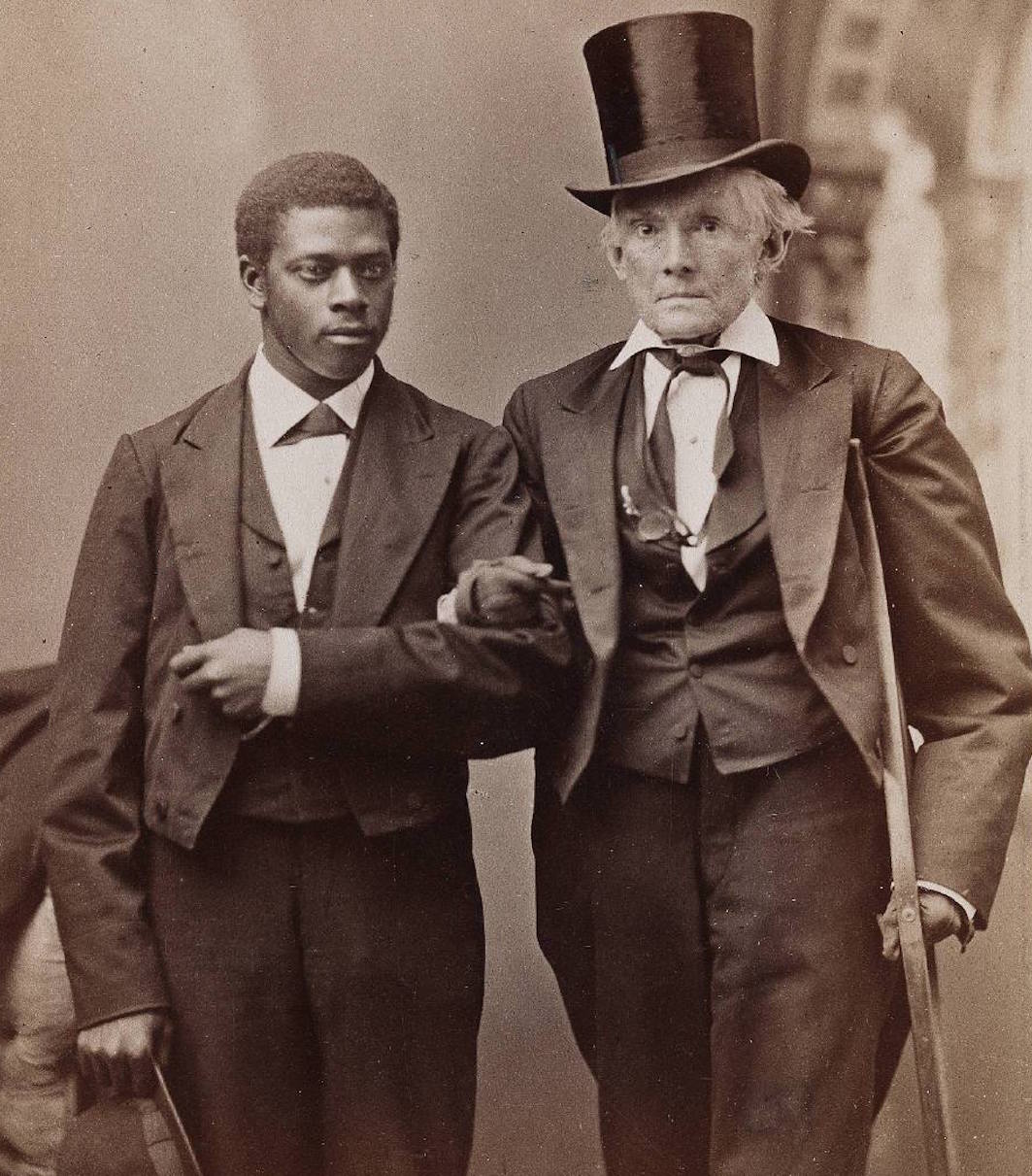

‘NOW THAT TAKES THE CAKE!’ This 1-minute silent clip, from 1903, is currently the oldest-known film of a drag performer. The dancers — one in striped pants, the other in a dress — were recorded in France by Louis Lumière. The dancer in a dress is Jack Brown, an American from Virginia. In the show, they performed a version of the cakewalk, a dance invented by enslaved people, and the precursor to vogueing.

My Discovery of the First Drag Queen

“We were the people who were not in the papers. We lived in the blank white spaces at the edges of print.”

— Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale

Channing Joseph, 7, far left, performing in a school play. Exact date and source unknown.

I was a queer little black boy, just like William Dorsey Swann.

The adults in my small Louisiana town were not much better than the kids who called me names. They were baffled by my total lack of interest in football and my odd fascination with art and the ballet.

I yearned to escape the skin I had been born in, and I sought refuge in stories and other forms of make-believe. I dreamed of growing up to be a masked superhero. I fantasized about wearing a Starfleet uniform and leading a spaceship through the stars. And in the bathroom mirror, afraid to death of being caught, I secretly tested my grandmother’s rust-toned lipstick and rouge, imagining myself a supermodel.

In the second grade, I got my first chance to be someone else when I was cast as a pilgrim in my school’s Thanksgiving play. I was excited for the chance to dress up and become a new character. It was also my first exposure to American history at school.

In that mythologized story about Europeans escaping religious persecution, American Indians were mentioned, but they were not central characters, despite having lived on the continent for thousands of years before the pilgrims’ arrival. The enslavement of Africans went unacknowledged, of course. And queer people, even if they had been thought about, had no place in a nice children’s play about how the United States began. The unmistakable message that I, and all the students of Bayou Woods Elementary School, got was that those kinds of people — people like me! — were not really part of the story of America.

In my youth, I dabbled in drag. In high school, I loved to play with glitter and eyeshadow and to paint my nails every color of the rainbow. Later, at Oberlin College, I signed up for a “how-to” drag course taught in the campus disco by a friend and fellow theater major.

In our nightclub classroom, we covered everything: how to apply foundation, how to walk in heels, how to strut down the runway, and, of course, how to vogue. Before I knew it, I was turning heads in a bright-orange boa and eight-inch, silver, platform heels. I had transformed from a boy in a dress into a queen, and I became the star of the college’s annual Drag Ball. (To my great delight, my picture was in the school paper two years in a row.)

I later discovered the existence of the House of Swann in 2005, under the most random and fortuitous of circumstances. After Oberlin, I gave up drag, deciding I needed to finally “get serious” about a career in writing. In 2004, I moved to New York City to study for a master’s degree in journalism at Columbia. Yet as I wandered through the stacks of Butler Library, I somehow found drag always lurking at the back of my mind. Maybe that is why — while researching a class assignment in my rather dry investigative reporting class — I stumbled upon an intriguing article from The Washington Post as I scoured online news databases for ideas.

“Negro Dive Raided,” the April 1888 headline read. “Thirteen Black Men Surprised at Supper and Arrested.”

It only got more interesting from there.

“An animated conversation, carried on in effeminate tones, was in progress as the officers approached the door,” the story went, “but when they opened it and the form of Lieut. Amiss was visible to the people in the room a panic ensued. A scramble was made for the windows and doors and some of the people jumped to the roofs of adjoining buildings. Others stripped off their dresses and danced about the room almost in a nude condition, while several, headed by a big negro named Dorsey, who was arrayed in a gorgeous dress of cream-colored satin, rushed towards the officers and tried to prevent their entering.”

“Who could this Dorsey have been?” I wondered, as a strange, new feeling rose up within me. I could not have said at the time what that feeling was. Yes, part of it, certainly, was curiosity. But the other part was something I had never felt before. It was something akin to validation. It was as if I had seen a fleeting glimpse of myself in history.

As I write these words, I wonder how different my childhood would have been if I had grown up in a world where my teachers talked about Swann and how his drag events helped to shape America.

Maybe I would not have felt like quite such a freak — and maybe I would not have wished so often that I had never been born.

I can still hear the black kids shouting: “Get out of here, you fag!”

“You ain’t nothing but a cocksucker, you nigger!” the white ones hollered.

But according to the history I learned, gay people hadn’t even existed in the nation’s past. Instead, I had been taught — like all American schoolchildren are — about Christopher Columbus and Ben Franklin and Thomas Jefferson and George Washington and Paul Revere. Those were the most important people one could learn about. As a child, I never questioned it. I accepted the world as it was.

I saved a copy of the article for later and got back to my school work.

For a decade, I put drag and William Dorsey Swann out of my mind, thinking that someone else more qualified would take on the subject. Instead, I turned my attention to my journalism, which has since kept me very busy. I wrote stories for The Atlantic and Entertainment Weekly, MTV, and CNN, and I edited them for TIME and VIBE. After years of freelancing, I became a staff editor and writer at The New York Sun and, for three years, at The New York Times, where I kept my adrenaline pumping covering breaking news, crime, education, and poverty in New York City. At The New York Times, I also helped edit numerous investigations, including one that led to the release of at least eight wrongfully convicted prisoners. I worked with Pulitzer Prize winners, shaping their groundbreaking stories. (These were the kind of folks I thought could someday write my Swann story.) Later, I moved to the West Coast to help lead the San Francisco bureau of The Associated Press, and after traveling throughout Japan on an international reporting fellowship from the Ford Foundation, I was recruited to be the editor-in-chief of SF Weekly, San Francisco’s flagship alternative newspaper. My stories have now appeared all over the world, from South Africa to New Zealand, reaching millions of people in print, online, on TV, on the radio, and, of course, on social media.

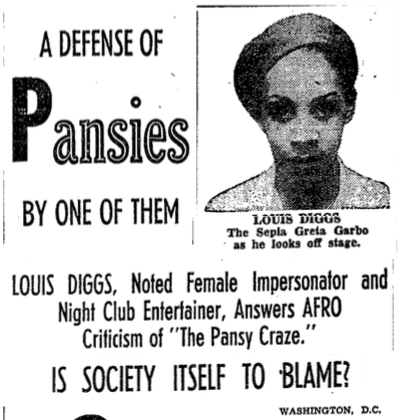

Yet through it all, I couldn’t shake the nagging feeling that I was neglecting an even more important story. In the midst of all my professional successes, I remained curious about Swann. Once every couple of years, I would do a Google search and find nothing. Unsatisfied, I would then scour the scholarly history journals, yearning to learn more about him. Eventually, I began to piece together details about his drag events in archival materials. Although I didn’t see any books or recent articles about Swann or nineteenth-century drag queens in the nation’s capital, I did find blog posts and other sites claiming falsely that drags balls began in Harlem in the 1920s and ’30s.

How could they be so wrong? I wondered. Didn’t they know about the courageous group of drag queens in the nation’s capital that had fought to create a space for themselves more than a half century before that? I became obsessed. I found myself reading all the academic literature on queer history, staying up through the night searching online archives of historical newspapers, census records, slave narratives, old diaries of Washington, D.C., and bizarre nineteenth-century medical journals. I was becoming an expert on the topic.

In 2015, I was assigned to write an opinion column for Truthdig, a progressive news site run by an amazing team of thoughtful, award-winning journalists. The assignment was to craft a piece on the controversy surrounding Roland Emmerich’s movie Stonewall. Critics had already called the film a “whitewash” for what they said was a failure to accurately represent people of color and the transgender community in the historic events depicted in the film.

I found myself asking if the film was even accurate in its essential premise: that the 1969 Stonewall uprising was the beginning of the fight for gay rights in America.

As I began reporting, I decided to include what I knew of William Dorsey Swann and his group in the piece. In the process, I spoke with leading historians whose work I had been studying for years. To my surprise, they had never heard of him or his group of pioneering American crossdressers.

When the column, titled “The Black Drag Queens Who Fought Before Stonewall,” was published, it received thousands of page views and shares. Martha Mendoza, a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner for her work exposing modern-day slavery in Southeast Asia and the unlawful killing of refugees during the Korean War, wrote to me to praise the piece. Soon, the groundbreaking historian Jonathan Ned Katz (author of Gay American History: Lesbians and Gay Men in the U.S.A. and Love Stories: Sex Between Men Before Homosexuality) reached out to tell me that my research was “a wonderful discovery.”

I have since heard from prominent gay historians across the country, from Kevin Mumford at the University of Illinois (author of Not Straight, Not White: Black Gay Men From the March on Washington to the AIDS Crisis) to Jessica Marie Johnson at Johns Hopkins (organizer of the Queering Slavery Working Group) to Michael Bronski at Harvard (author of A Queer History of the United States), none of whom had previously heard anything about Swann and his drag dances.

Slowly, it dawned on me: I was becoming the historian that I had been waiting for.

I now live in sunny Los Angeles, where I am a member of the journalism faculty at the University of Southern California. In my classes, I instruct young reporters in how to think and write about sexuality, gender, and ethnic identity in ways that are sensitive, smart, and historically accurate.

Whenever I can, I mention Swann. I can’t help it. He has so much to teach us, and as a former queer little black boy, I want the world to know that people like him — and like me — have always been part of the American story.

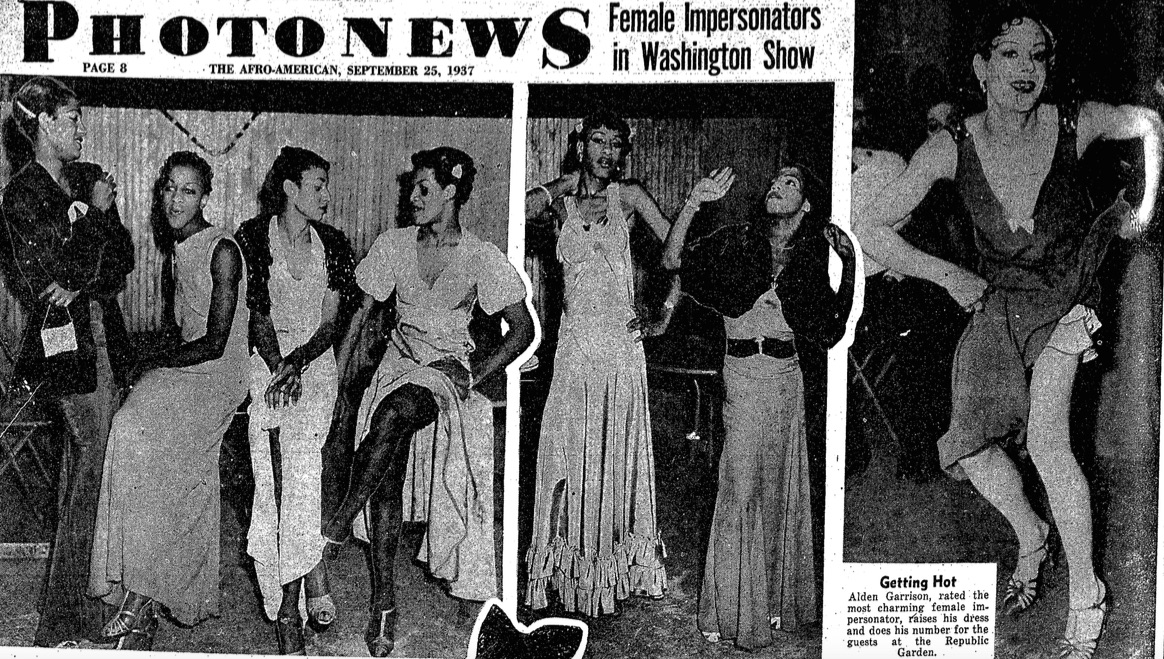

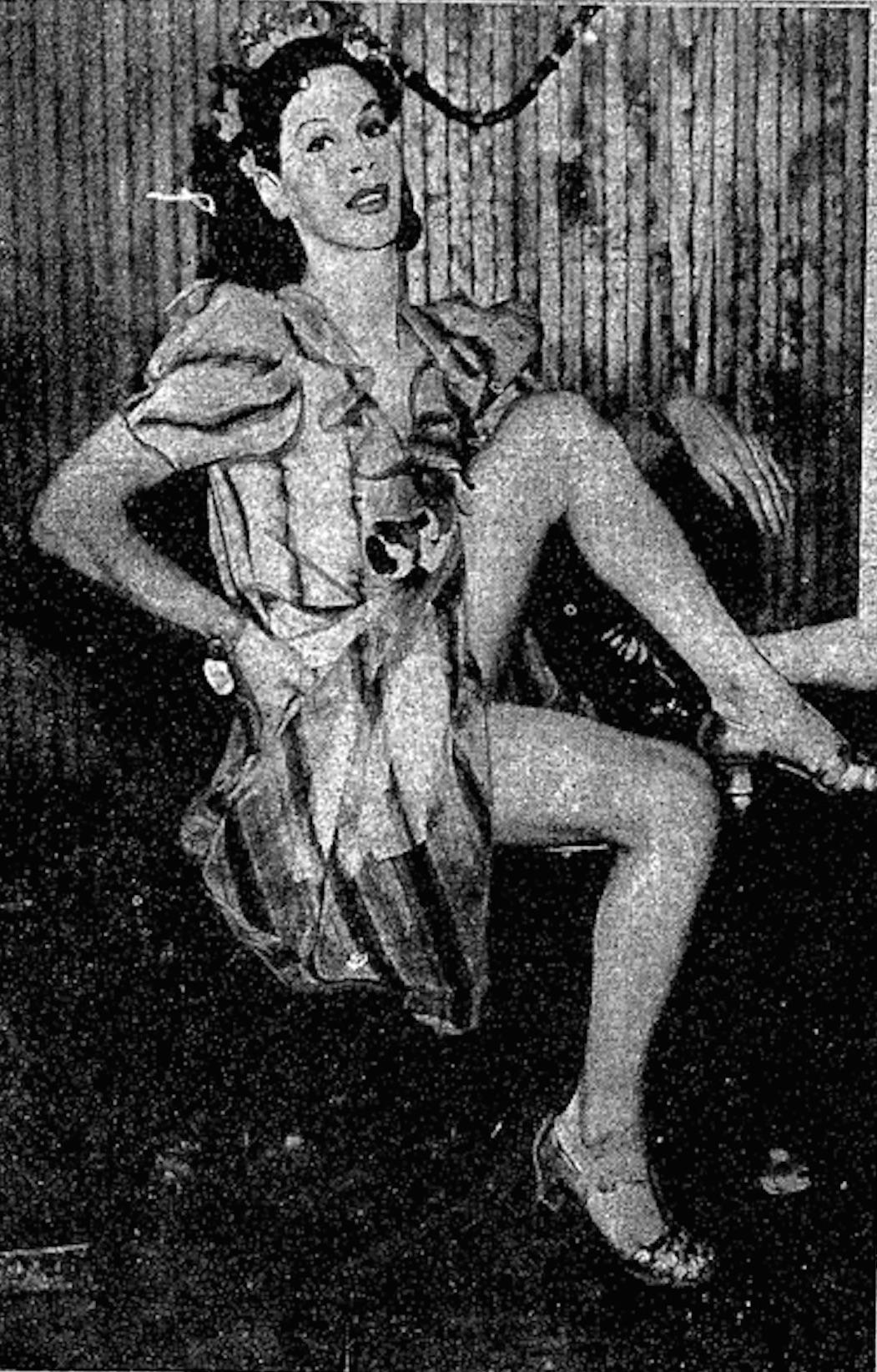

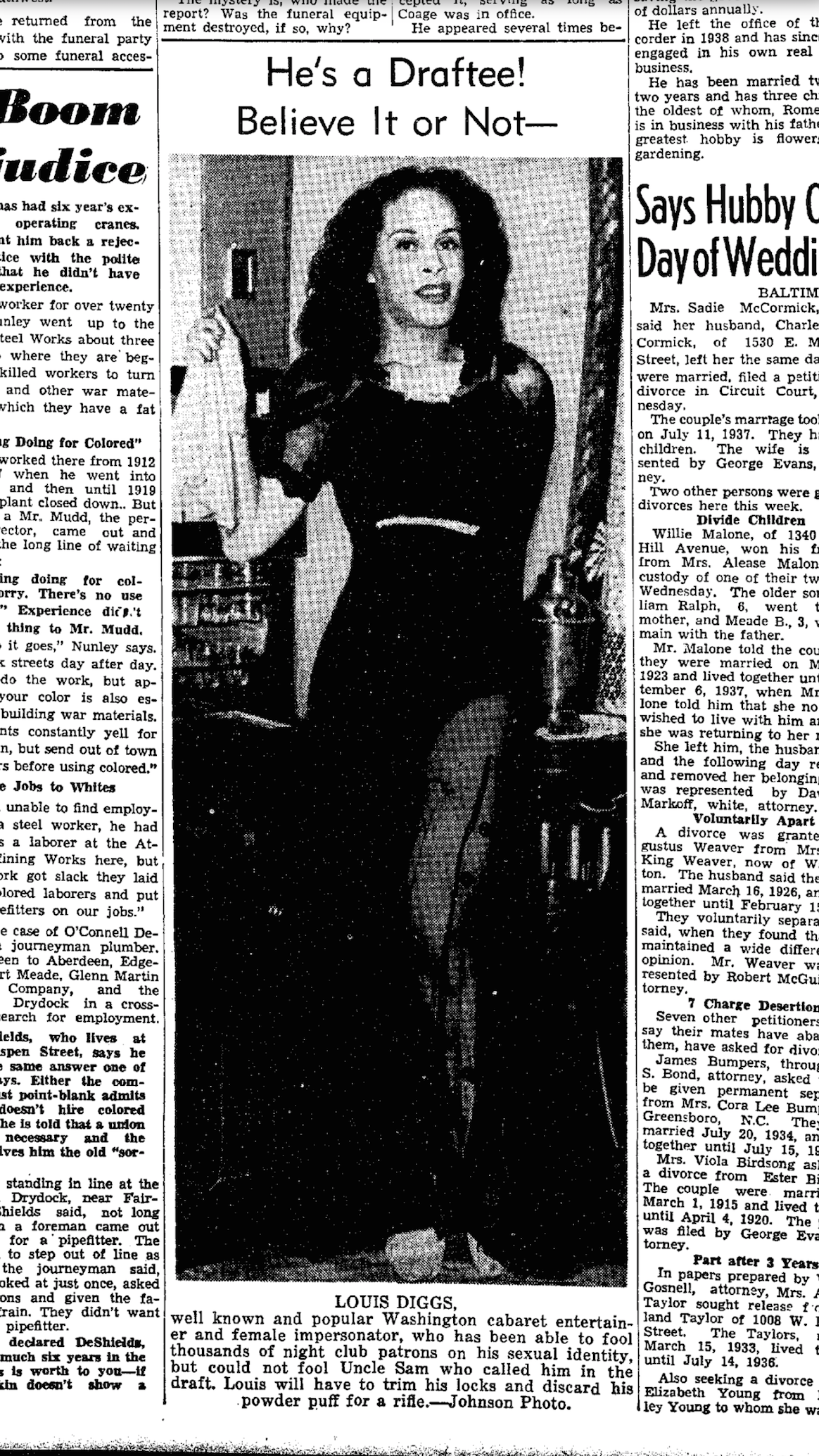

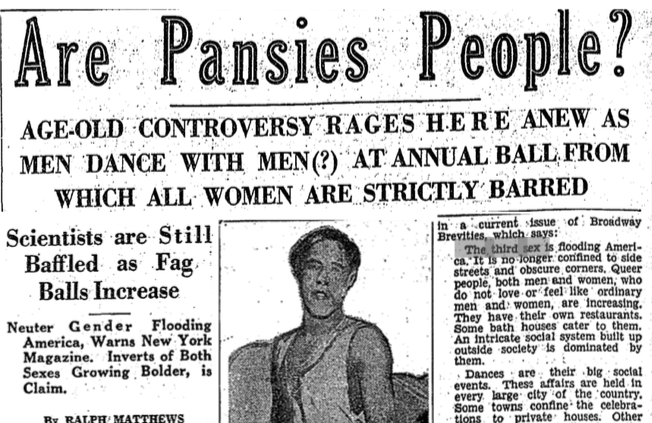

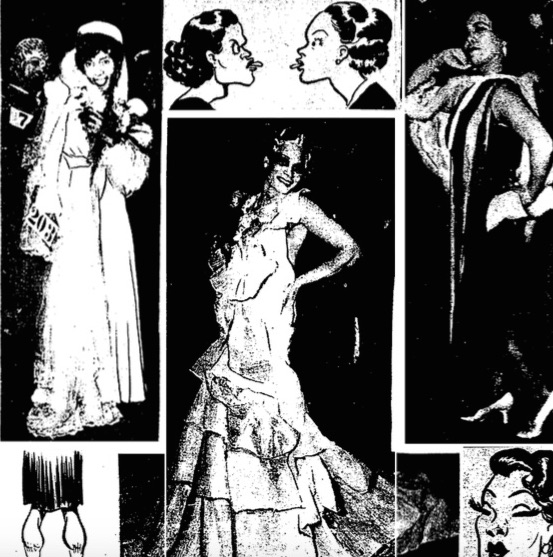

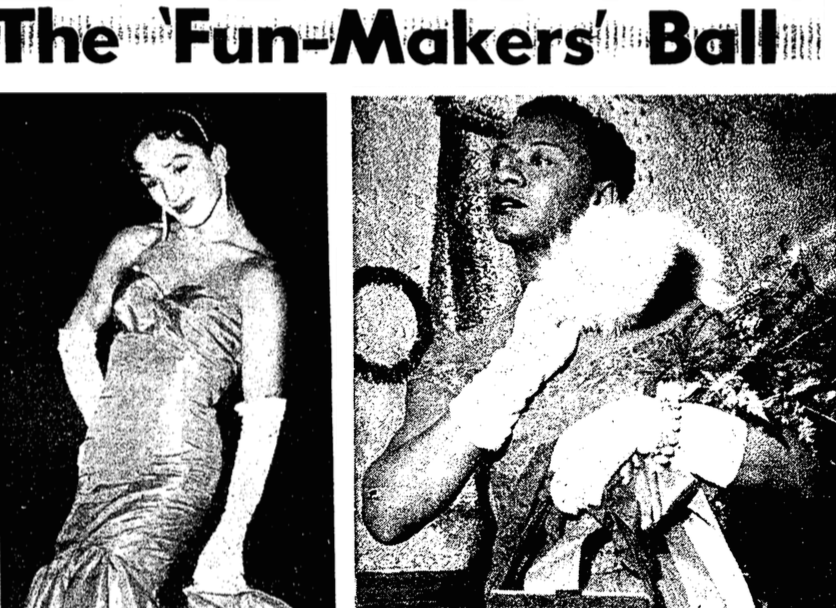

*Though several articles written by amateur and professional historians assert that New York’s Hamilton Lodge balls started in the 1860s — including one posted on the website of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History — the Columbia University historian George Chauncey disproved this theory in the 1990s. Expanding on Chauncey’s work, my own research indicates definitively that the Hamilton Lodge held its first masquerade ball in 1883, catering not to male crossdressers but to conservative members of the black middle class. These first parties were more akin to upscale Halloween parties of today. It took more than forty years before drag queens began to attend the fraternal group’s annual ball in large enough numbers that a New York Age reporter finally observed, in 1927, how “curiously noticeable” it was that the male attendees wore dresses, “with very few exceptions.”

The First Queer American Hero

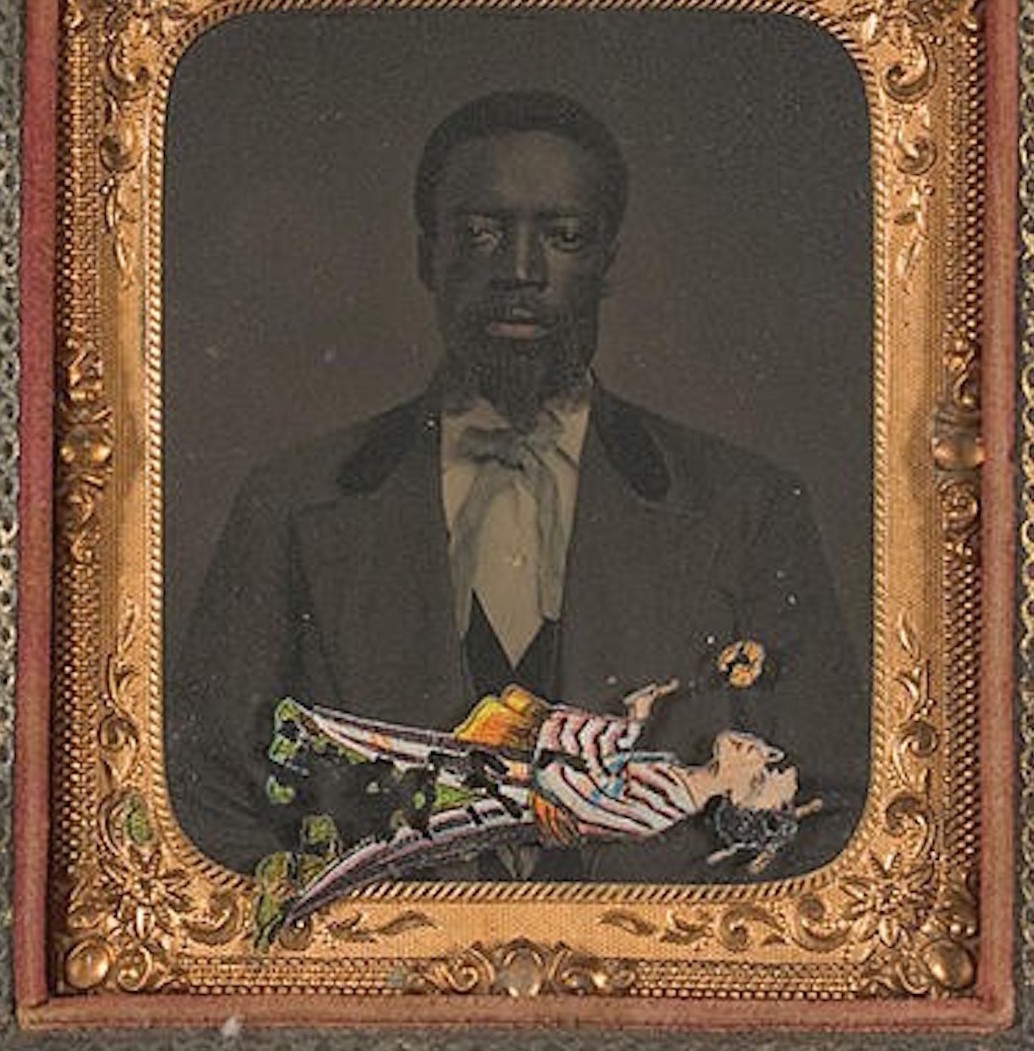

About House of Swann: Where Slaves Became Queens — and Changed the World, by Channing Gerard Joseph

Forthcoming from Crown and Picador.

It was April 12, 1888.

When the police burst through the door of the two-story residence in northwest Washington, D.C., just half a mile from the White House, they discovered dozens of black men dancing together there, wearing silk and satin dresses made “according to the latest fashions.” Most of them were former slaves or the children of slaves.

As soon as the partygoers saw the officers, the dancing suddenly stopped. Instead, the attendees looked on in shock for a brief moment before scurrying to make their getaway. Many of them, the newspapers later reported, struggled to strip off their garments, their ribbons, and their “wigs of long, wavy hair.” Others raced immediately to the back doors or leapt out of second-floor windows and onto the roofs of nearby buildings. The sound of shattering glass awakened the neighbors as one unfortunate guest crashed through a skylight.

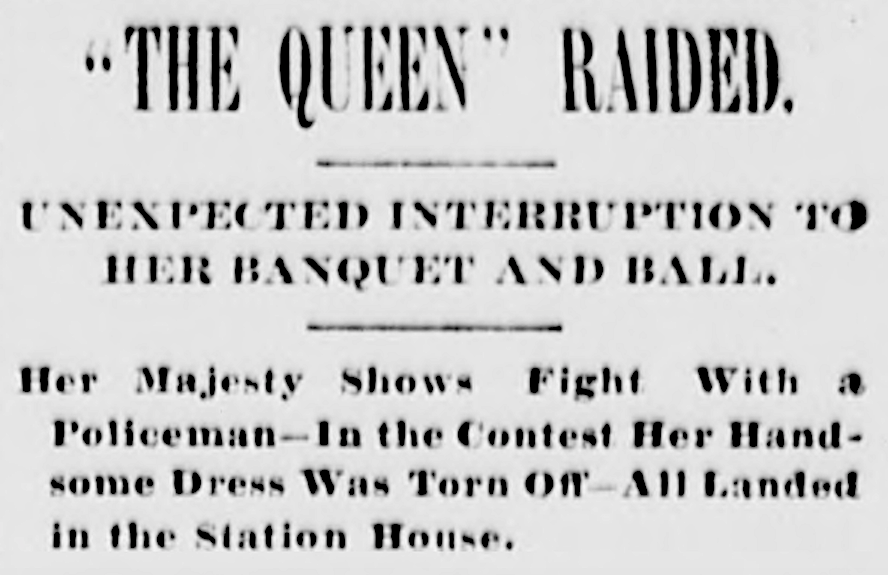

William Dorsey Swann, the self-proclaimed “queen” of the gathering, had no intention of running away. It was his thirtieth birthday celebration, and according to The Washington Post, he was “arrayed in a gorgeous dress of cream-colored satin.” Unlike the others, he ran frantically toward the officers in a vain attempt to keep them from entering the room. “The queen stood in an attitude of royal defiance,” The National Republican noted on its front page. “Bursting with rage” as he stared down the invaders, Swann told them haughtily, “You is no gentlemen.”

A brawl ensued, and his “handsome” gown was torn to shreds. Half-naked, he was then taken to jail and charged with the crime of “being a suspicious character.” “It is safe to assert,” one commentator wrote after the raid, “that the number living as do those who were taken into custody last night must be exceedingly small.” In 2018, it is easy to forget that in the late nineteenth century, hardly anyone had ever laid eyes on men in dresses. That is why, The Post observed, there was “considerable excitement on the streets and a crowd of about 400 people followed the prisoners to the station house.” Drag queens were more than a novelty in the 1880s. They were a shock to the system.

That night, Swann was arrested with 12 other African-American men, but according to one report, as many as 17 other men may have escaped. As was the custom, the local papers printed the names of those who were detained. Ironically, acts of public shaming like this one are the only reason we now know who Swann was. The identities and stories of the men who escaped capture have been lost to history.

The surprise raid of April 12, 1888, was neither the first nor the last time that William Dorsey Swann was carried away in the police wagon for organizing drag balls in private homes in the nation’s capital. But his decision to fight that night rather than to submit passively to his arrest marks one of the earliest-known instances of violent resistance in the name of gay rights. Only one such prior event is recorded, and that was in England in the 1700s. According to the historian Rictor Norton, a 1727 riot in England over the unjust punishment of a convicted “sodomite” is the earliest-known violent protest in support of what we would now call LGBTQ rights.

Beginning as early as 1882, Swann was the first person to dub himself a queen of drag, the first to create an organization for queer liberation, and the first to urge the members of his queer community to hold their heads up high and fight for their rightful place in the country they and their ancestors helped to build. In addition, in 1896, Swann became the first and only known activist to seek a presidential pardon after being arrested and convicted for holding a drag event.

Swann’s era can be characterized as a time for queer people to carve out an identity and to build a secretive community. Later, the 1920s and ’30s can be seen as a time when that community becomes visible to the world in a proud and publicly ostentatious way for the first time. Stonewall, rather than being the start of the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement, represents a third stage in this progression: the explicit call for fair treatment and equal rights — a call that Swann himself made in 1896 when he became the first American to take legal and political action in defense of queer community by demanding that President Grover Cleveland pardon him for his efforts to create space for his burgeoning community.

More than a century later, the Houses of the contemporary ballroom scene — still led by House Mothers, and organized around beauty and dance contests — maintain the same basic format as the House of Swann.

The Rise of 'Queer' Activism

Though no one in Swann’s cohort can possibly know, queer ancestors once were accepted and celebrated by cultures throughout Africa. According to some ancient mythologies, queer people were endowed with special cosmic gifts, and were tasked with being “gatekeepers” who helped to guard the universe from descending into chaos.

Swann, an American version of the mythological gatekeeper who worked to keep his own community protected from the chaos of a hostile world, became the first self-described queen of drag, the first to create an organization for queer liberation, and the first to urge the members of his queer community to hold their heads up high and fight for their rightful place in the country they and their ancestors helped to build.

In Swann’s era, iconic Washington residents like Frederick Douglass, Sara Spencer, and others fought for equality among whites and blacks, women and men. But Swann fought for something else — the freedom to love and be loved outside of marriage, the freedom of a man to love another man openly, and the freedom to be a woman, if only for a night.

I use the word “queer,” but Swann and his friends live in a time long before positive identities like “gay,” “bisexual,” and “transgender” have been clarified and named. They live their entire lives without ever hearing these terms used as they are today. The word “queer,” which they do know, simply means “unusual” and is always used pejoratively. Though some members of the “House of Swann” used feminine names while in drag, all of the thirty or so documented group members continued to dress as men and to use and be known by masculine names and pronouns throughout their lives.

Swann’s defiance was not only an act of self-preservation but also an attempt to preserve the livelihoods and freedom of his fellow drag queens, who faced jail time as well as the possibility of economic and social ruin from being outed in the newspapers. Though unknown for more than a century before I rediscovered him in 2005, his bravery and activism made him an irresistibly compelling example in his own lifetime — not only for his D.C. party guests but also for those who heard reminiscences about his unforgettable gatherings years later in other cities across the nation.

Resisting raids by police, surveillance by doctors, and possible infiltration by spies in the 1880s and ’90s, Swann’s rebellious group of butlers, messengers, coachmen, and cooks risked their livelihoods and reputations to carve out a space for themselves in the nineteenth-century capital, at the center of American power, prestige, and influence. They were all the more remarkable because they lived in an era before there were any legal defense groups or political organizations willing to come to their defense.

Over the course of the book, Swann’s extraordinary life unfold, from his brutal childhood in slave-holding Civil War-era Maryland and his coming of age in the Reconstruction era — discovering his sexuality in a world that still lacked the words to describe what he was feeling — to his heyday as the queen of Washington’s queer underground. Though he finds himself increasingly hounded by all manner of authorities and fellow citizens throughout his frequently nail-biting journey — from heavy-handed judges and hostile white neighbors to curious doctors and disapproving members of the African-American elite — he manages, seemingly against all odds, to cultivate a thriving network of drag queens and allies where none had existed before. Queer black men — like Swann and his associates — experience, perhaps for the first time in history, the joy of friendship, loyalty, and self-expression in a nurturing community of like-minded souls. Tragically, some — like Swann’s friend Pierre Lafayette and eventually even Swann himself — find the odds are insurmountably stacked against them. But by the end of the story, as Swann’s confidant Jacob Bayard suspects, their victory is certain and, though they did not live to see it, their legacy is undeniable.

Though the Stonewall uprising of 1969 is often touted as the beginning of the fight for gay liberation, Swann’s courageous example forces us to rethink everything we thought we knew about the gay rights movement — when it began, where, and who its leaders were. Indeed, as members of the first-known self-organized queer group in America, Swann’s followers helped lay the crucial foundations of self-acceptance, solidarity, courage, and confidence that eventually made Stonewall, LGBTQ pride, and marriage equality possible more than 100 years later.

A Living Legacy

Swann’s organization is also the earliest-known predecessor of the contemporary houses publicized in Jennie Livingston’s acclaimed 1990 documentary on New York’s “ballroom” community, Paris Is Burning, and more recently on FX’s critically acclaimed TV series Pose. Just like Swann’s group, twenty-first-century houses are led by “maternal” male figures — called house mothers — who serve as mentors in life as well as in community activism, art, fashion, and dance. Today, nearly a century and a half after Swann’s balls began, there are now far too many houses to list, all throughout the globe — the House of LaBeija, the House of Xtravaganza, the House of Balenciaga, the House of Milan, the House of Pendavis, the Legendary House of Ninja, and on and on. But Swann’s powerful legacy is reflected not only in the continued existence of houses of the same form. It is also apparent all across popular culture, wielded by figures gay and straight, from Madonna’s ballroom-inspired “Vogue” to Beyoncé’s drag-inspired album I Am... Sasha Fierce.

RuPaul’s Drag Race, a reality show whose format is largely based on the structure of a house, is now an international phenomenon, bringing drag culture into homes from Sweden to South America.

The book’s historical scope is unique. While many well-known narrative histories of LGBTQ life focus on Stonewall, or on the AIDS crisis of the 1980s, this story centers on the period between 1853 and 1902, detailing the remarkable origin of drag culture, and how it eventually evolved from an obscure hobby of outcasts to an international phenomenon whose influence is seen throughout pop culture — in best-selling books, TV shows, and blockbuster movies — while being celebrated daily in queer communities around the world.

The book also revives a fascinating yet largely forgotten moment in history. The plot occurs during a historical period that remains fuzzy in the American imagination because we simply see it as the hyphen between the Civil War and World War I, yet it was a time of immense social turmoil and cultural change. Three of the four assassinations of American presidents in history occur during the nearly fifty-year time span that constitutes the book’s major action. Slavery is abolished. In anger, white citizens attack black voters, throw bricks, and set fire to buildings. The first black men in the nation are elected to office, disproving hundreds of years of racist propaganda. Though the war that killed more than 600,000 Americans is over, many are still willing to kill and die for all manner of personal and political causes, and sometimes for no cause at all. The Ku Klux Klan is formed. White women suffragists, still denied citizenship rights by leaders who laugh at their petitions, protest in a series of women’s marches in the streets of a capital filled with “hack” drivers of horse-drawn carriages offering 75-cent rides.

Washington during Swann’s day is “the most interesting and attractive city in America” — sometimes even “the Paris of America” — its white-marble sublimity marred only by the networks of uncounted shanties and rickety cabins that sprung up during the war in the crevices between and behind the mansions of the capital’s elite. Masquerade balls are popular, as are theatrical comedies performed by white actors portraying plantation life in black face paint. The commercial telephone is invented. So are the phonograph and the automobile. The cakewalk, a dance developed on plantations, takes the world by storm. Ragtime, jazz’s musical predecessor, is invented. The Dirty Dozen, the children’s game about who can hurl the worst insult against an opponent’s mother, develops into a high art, laying the groundwork for hip-hop.

Meanwhile, an array of well-known personalities is active at this time, each playing a part in the story, including: Red Cross founder Clara Barton; legendary abolitionists Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs; feminist icons Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Mary Church Terrell; the renowned architect Frederick Law Olmsted; U.S. presidents James Garfield, Abraham Lincoln, Grover Cleveland, William McKinley, and James Buchanan; Civil War traitors Jefferson Davis and Alexander H. Stephens; and even presidential assassins John Wilkes Booth, Charles Guiteau, and Leon Czolgosz.

For years, Swann was a resident servant in the home of William Wade Dudley — a celebrated Union Army war veteran who later became a controversial political operative and the treasurer of the Republican National Committee. In the early 1880s, Swann also worked for Sara Spencer, a pioneering women’s rights activist who was the lead plaintiff in a landmark court case establishing that American women were indeed citizens under the law. His relationship with Spencer is especially interesting because they were each considered gender misfits. In the nineteenth-century, a queer man and a heterosexual woman who supported gender equality would have both been tagged with the same derogatory label: “the third sex.”

Recovering Forgotten Stories

Much of the LGBTQ past in America was intentionally wiped away, obscured, and ignored for centuries, and there is a persistent myth that no significant primary sources for LGBTQ history even exist. The clues that survived were often so scattered that it was difficult to know where to begin. But with the advent of more advanced research tools, that era may now be behind us. Thus, the book is an effort to at last put those pieces back into place, and to revive the spirits of our long-forgotten gay heroes. The main star of the book, though, is Swann himself. William Dorsey Swann was totally unique for his time. He not only inspired a group of both white and black men to coalesce around him for fun, fashion, and friendship — society’s laws and social conventions be damned — he convinced them to risk their livelihoods and reputations to follow his example.

Unlike the men who met for anonymous sex in the overgrown bushes of the city’s Lafayette Park (just north of the White House), or the effeminate male performers and sex workers who were paid to amuse and shock the crowds of straight guests at New York’s “fairy resorts” in the 1890s, the men who attended Swann’s gatherings experienced something unusual for the time period: Swann offered his associates an opportunity to transgress nineteenth-century social norms in a supportive and primarily nonsexual environment. As they enjoyed music, dancing, food, and drink, they had the opportunity to deepen social bonds without the expectation of sex, the need to prostitute themselves, or the pressure to perform for an audience of leering outsiders.

Though his methods were unconventional (he was not averse to petty theft or fist fights), Swann’s efforts to build a close-knit community of queer activists in the early 1880s — when there was no other such group anywhere in the world — makes him the first gay American hero, and his “House of Swann” — the group of former slaves and rebel drag queens that he led in Washington, D.C. — is the earliest-documented gay rights organization, operating for at least two decades in the shadows of our nation’s most powerful people and institutions. His social gatherings occurred at a time when people who violated sexual and gender norms were often harshly punished. Legal, political, and religious institutions, as sternly as they viewed miscegenation, were arguably more accepting of racial mixing than of same-sex attraction or romance.

No other activist organization by and for queer people seems to have been formed until the German physician Magnus Hirschfeld created his Scientific-Humanitarian Committee in Berlin in 1897. Though the great American poet Walt Whitman boldly wrote of his bisexual desires in the 1855 collection Leaves of Grass, he was not the leader of a movement. While the writer Karl Heinrich Ulrichs began a campaign to repeal Prussian anti-sodomy laws in the 1860s, Ulrichs was a loner and failed to build a coalition of supporters and allies around his ideas, even though crossdressers commonly mixed into the crowds at European masquerade balls. And although male members of the British aristocracy were put on trial in 1870 for wearing women’s clothes in public (the case that put the word “drag” in the dictionary), they did not seek to forster an affirming community. Nor did they see themselves as activists: They took no interest in fighting the authorities or publicly speaking out against society’s disapproval.

Swann’s parties occasionally included some privileged white men whose names are still not known, some of whom were called as witnesses when the black men were put on trial. However, the majority of those who risked their reputations to attend his dances were working-class African-Americans — almost all of whom had lived through the Civil War, and many of whom had been born into slavery. They acted out of a deep yearning for self-expression, but they also acted, in part, because of the overwhelming sense of possibility that African-Americans’ recent freedom promised. As residents of the capital, they were immersed in an atmosphere of constant, lively political debate and protest. Swann, in particular, was heavily influenced by his close association with the power players for whom he worked, and whom he inspired to become his allies.

*James Buchanan is still the only U.S. president to have been a lifelong bachelor. In his day, tongues wagged in Washington over the “conspicuous intimacy”; he shared with William Rufus King, an Alabama senator who would later become vice president under Franklin Pierce. Though King died of tuberculosis in 1853 — after only a month and a half in the vice presidency — he and Buchanan had lived together in the decade prior. In fact, they were so inseparable that gossips dubbed them “Aunt Fancy” and “Miss Nancy,” and joked that King was Buchanan’s “better half.”